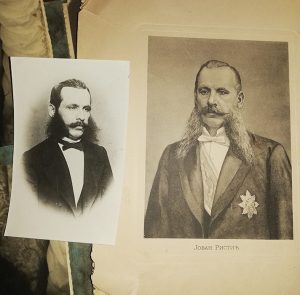

Jovan Ristić

Date of birth January 16th 1831

Place of birth – Kragujevac, Principality of Serbia

Date of death – September 4th 1899 (68 years)

Place of death – Belgrade, Serbian Kingdom

Prime Minister

Jovan Ristić (Kragujevac, January 4th (Julian calendar)/January 16th (Gregorian calendar) 1831 – Belgrade, August 23rd (Julian)/September 4th (Gregorian) was Serbian politician, diplomat and historian. Besides Ilija Garašanin and Nikola Pašić, Ristić is one of the greatest Serbian diplomats of the 19th century. He was founder and leader of the Liberal party. He has became one of the most powerful persons in Serbian politics since 1868 to 1893. Ristić had many crucial roles in Serbia and pacticaly, he had power, he was éminence grise.

Ristić was twice nominated for the council of regency of two underage rulers, firstly, in the name of Prince Milan Obrenović, and afterwards, in the name of his son, King Aleksandar Obrenović. He managed to take advantage of Milan’s age and political inexperience of other regents and adopt Regency constitution. Ristić was representative of the Principality of Serbia at the Congress of Berlin, where the independance of Serbia was proclaimed.

He was a regular member of the Serbian royal academy (today called SANU) and for a certain period of time, the President of the Academy in 1899.

Jovan Ristić was a man with extraordinary intelligence, a great figure of Serbian politics of the 19th century. He was the only Serbian diplomat who was able to communicate to European diplomats on an equal basis.

He was born in 1831 in Kragujevac, in a poor family, from the father Rista and mother Marija. His excellent success in Elementary school convinced a family friend to send Jovan to High school in Belgrade.

During his stay in Belgrade, Jovan became an outstanding member of the Serbian youth association, quasi-political student association which thrived after the event of 1848. Young Ristić was one of the few people from Serbia who attended Mayan parliament.

After graduating Belgrade Licej (University) with Serbian state scholarship in 1852, Ristić refused to study theology in Russia. One of the persons who accepted a scholarship to study in Russia was future Belgradian metropolite Mihailo who will later become Ristić’s ally in relatively liberal pro-russian movement in the second half of the century. In 1849, Ristić started studies in Berlin, moreover, he gained the title of doctor of philosophy in Heidelberg. Afterwards, he continued studies at prestigious Parisian Sorbona. In Germany, he was mentored by historian Leopold Von Ranke, furthermore, he planned to continue his career as a historian. Nevertheless, he was not able to become professor at Belgrade Licej.

n 1854, Jovan became a member of the council of regents: he started working in the Ministry of internal affairs which was governed by influential political leader Ilija Garašanin.

Young Ristić was strongly influenced by bureaucracy school. He was convinced it was a place which allows people to rule the world. Soon after, he married Sofija, daughter of the rich Belgrade merchant, Hadži Toma. This marriage brought him, besides finances, affection of Serbian Princes of Obrenović dynasty.

During one period, while working as an editor at „Serbian journal“, Ristić made efforts to bring popularity of Shakespere in Serbia.

In 1861, Garašanin sent Ristić to Serbian mission in Rome. It was the beginning of his successful diplomatic career. During negotiations with Turks in 1867, he managed to negotiate the withdrawal of the Turkish troops from the Serbian fortresses. Upon his return to Belgrade, he was elected as a Minister of foreign affairs. When Prince Mihailo redirected foreign policy in 1867, leaning less on Russia for attendance and dismissed Garašanin from the position of Prime Minister, Ristić was placed on that position for a while. However, Ristić did not wish the Conservatives to represent the government. He felt that if he could not form a government on his own, without his like-minded leaders like Jevrem Grujić, the leader of the Holyandrej Liberals, then he would not form one at all. Prince Mihailo found this request offensive and outrageous, so he appointed Conservative Nikola Hristić as President of the Council of Ministers.

Jovan Ristić. Milivoje Blaznavac and Jovan Gavrilović were appointed as members of the council of regency until Prince Milan Obrenović comes of age.

Unlike the more radical liberals, Ristić’s model of a regulated state were not the United Kingdom or France, but Prutenia. He believed that Serbia needed a two-houses parliament.

In foreign policy, Ristić tried to unite the Serbian people into one state, as Piedmont did in Italy and Prussia in Germany, and to reduce Serbia’s dependence on Austria and Russia. The Grand National Assembly, which endorsed Milan’s election as prince, adopted, without consideration, a seventeen-point agenda, with several liberal demands. Ristić immediately realized that he could use the authority of the Grand National Assembly’s decision to reshape the administration in Serbia. In December 1868, he convened delegates to the „Nikoljski“ Committee to discuss whether Serbia needed a new constitution to replace the Turkish constitution of 1838, which Prince Mihailo amended in 1861. Delegates agreed that a new constitution was needed in which the National Assembly would be given a larger role, but the question of the organization of the assembly remained unresolved. Ristić proposed a two-houses assembly with an upper house that would consist of a State Council with members appointed by the government for a limited period and a lower house.

More radical liberals advocated one-house assembly that would be fully elected. „Nikoljski“ Board was dissolved without a clear decision on the organization of the assembly, but also with a clear conclusion on the need to adopt a new constitution. Ristić used this to convene the Grand National Assembly in Kragujevac. Unlike the more liberal Belgrade, Kragujevac was still a patriarchal milieu and delegates to the Grand National Assembly were generally local illiterate peasants more willing to accept what the government ordered.

The draft of the new constitution was written by Ristić himself. The new constitution, called the Regency Constitution, was adopted in contrary to the Turkish constitution which did not allow the constitution to be changed during the Prince’s underage.

Unsure, Prince Milan did not like Ristić, nevertheless, he was afraid of him. He preferred another diplomat, Jovan Marinović. Because he did not meddle into power. So there was competition between the two personalities, however, Marinović was not courageous and he was withdrawing. Thanks to Ristić, Serbia gained independence at the Berlin Congress.

Since the Serbo-Turkish War of 1877 – 1878 was successful for the Serbian army and it seemed as there were good chances of achieving Serbia’s political goals. It was up to the Ristić’s government to decide on Serbia’s military demands, which would be based on these Serbo-Russian victories. For this purpose, Prince Milan and the Serbian government have selected Ristić as the longtime fighter for Serbia’s national policy.

Serbo-Bulgarian quarrels, mostly around borders, caused by the light-headedness and pro-Bulgarian bias of responsible Russian officials, have developed into deadly hostility. Prince Cherkasky supported Bulgarian pretensions. He designates the entire area occupied by Serbian troops as Bulgarian, assigning to Bulgaria Prizren and Priština and even the district of Niš.

Although never implemented, the San Stefano Agreement had far-reaching consequences for the South Slavs and their relations with Russia. The agreement gave Serbia independence, but only part of its territorial requirements were fulfilled. For the Serbian public and political leaders, this was a great injustice, imposed by the Russians, whose reasons could not be understood by the Serbs. Ristić was angered by San Stefano decisions. He saw the opportunity for Serbia to emerge from an almost hopeless situation in the dissatisfaction of Vienna and London with the San Stefano Agreement. Two major powers were determined to obliterate the agreement, especially its key: Greater Bulgaria. Serbia’s military victories and Ristić’s skillful diplomacy made it possible to obtain Russia’s agreement to maintain the current military situation, until a definitive solution was reached.

“We must not consent to the role of pawn we have been given,” Ristić wrote to the head of the Serbian General Staff, Kosta Protić, in March 1878.

The San Stefano Agreement marked a major shift in Serbia’s foreign policy orientation, with Prince Milan and Foreign Minister Ristić playing the leading role. Soon, Ristić will go to Vienna, then to Berlin to defend Serbian citizens with Foreign Minister Andrashi and Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. These negotiations will mark the culmination of Ristić’s diplomatic career and bring significant benefit to Serbia.

Until San Stefano, Prince Milan was blindly loyal to Russia, seeing in the Emperor his natural defender. When he saw that the two wars of Serbia and Turkey resulted in the creation of a great Bulgaria as a major result, the Prince realized that Serbian foreign policy was based on dangerous Slovenian sentimentality. He decided to take a new direction, which would rest solely with Serbia’s interests. Without humiliation for Serbia and its government, Ristić discreetly and cautiously made a shift towards Austrian foreign policy. Avoiding haste and recklessness, he sought Austrian protection and support, receiving it without offending Russia, which he still counted on during his Viennese mission and at the Berlin Congress.

Most of the decisions, which were confirmed by the Berlin Agreement, were made unofficially, behind closed doors. Foreign Minister Ristić played a key and positive role. He was assisted by envoy Kosta Cukić and together they were the most capable Serbia had at the time. Ristić’s position was difficult and delicate: pressured by Vienna to leave the territories in the west, and from Russia to leave the areas around Pirot and Trn to Bulgaria in the east. He struggled to secure adequate profits for Serbia while maintaining friendly relations with both powers. Serbia did very well in Berlin, having gained a quarter more territory. Of all Balkan diplomats, only Ristić, who made a modest appearance at the congress, got everything that was needed for Serbia without offending any power and leaving with everyone in good relations. By taking control of the southern Moravian valley, Serbia became the ruler of the main routes from Europe to the Balkans, and the Vardar Valley was opened. Ristić successfully completed Serbia’s fight with the Ottoman Empire. He also made a fundamental contribution to the constitutional development of Serbia with his decisive role in the drafting of the constitution of 1869 and 1888. These documents encouraged the strengthening of democratic institutions in Serbia and highlighted it in the forefront of the Balkan countries.

For all the aforementioned credits, Ristić deserves to be one of the greatest diplomats and scholars of Serbia in the 19th century.

Jovan Ristić was interaste in history as well and wrote:

External relations of Serbia from 1848-1872

Diplomatic History of Serbia 1875 – 1878

He wrote one of the first histories of Serbian literature

(Retrieved from Wikipedia, 2019)